Design ChatGPT, or a ChatGPT like system.

You're asked to build and deploy a conversational AI system (like ChatGPT). The system's core purpose is to interpret user-provided prompts, generate relevant and coherent responses, and maintain near-real-time performance—even at scale with potentially high volumes of user queries.

We will solve this using our PADME framework.

Problem Statement

Recall our goal: clarify requirements, define clear business objectives, translate into ML tasks, and establish measurable success criteria.

Clarifying Questions

You're tasked with developing a ChatGPT-like system. First, clarify exactly what the interviewer expects. If uncertain, consider existing ChatGPT functionality and ask targeted questions, such as:

- Which languages should the app support?

- How much data do we have?

- Are we assuming fine-tuning an existing model, or is retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) in scope?

- What modalities (e.g., text, images, audio) will the app support?

- Should the ChatGPT system maintain context across multiple conversations?

Business Objectives

Identify clearly why the system is being built and how success will be measured. Important questions include:

- What's the primary purpose? Is it for customer service, content generation, question answering, or another use case?

- How will success be quantified? Examples might include response time, user satisfaction, or reduced support ticket volumes.

- Is the application targeting specific industries, such as healthcare, finance, or retail?

- Does the chatbot require domain-specific knowledge or adherence to compliance regulations?

Assume the chatbot is intended for question-and-answer interactions in English, without multimodal capabilities, but capable of maintaining conversational context. The business goals include 24/7 availability, cost reduction, consistent information delivery, and collecting data for continual system improvement.

ML Task

With these clarified requirements, the ML task is designing a supervised learning chatbot, likely involving fine-tuning a large language model (LLM) optimized for conversational interactions. Since it's language-only, focus exclusively on NLP capabilities. The task involves maintaining statefulness across multiple user interactions.

Success Criteria

Establish clear, measurable criteria aligned with both technical and business objectives:

- System availability: Chatbot operational 24/7.

- Efficiency: Reduction in average response times and overall operational costs.

- Consistency and accuracy: High user satisfaction rates, measurable through surveys or user feedback.

- Data-driven improvements: Effective data collection enabling continuous improvement through retraining and model updates.

Approach Outline

Before diving into solving the problem, you'll want to outline your approach to the interviewer. Start by mentioning a high-level overview of what will go through in the interview.

- Data

- Modeling

- Evaluation

- Infrastructure Not every ML System Design interview will cover the infra, some are focused solely on ML knowledge.*

Before diving into the problem, outline your approach to the interviewer using our PADME framework: Problem Definition, Approach Outline, Data, Modeling, and Evaluation, plus Infrastructure considerations.

A ChatGPT-like system transforms user queries into human-like responses while maintaining conversation context across multiple turns. Our solution will need to scale to millions of users while providing consistent, high-quality responses.

For data, we'll need extensive text corpora for pretraining and curated instruction datasets for fine-tuning. We'll explain how these are processed and tokenized, and design a runtime architecture that efficiently stores user profiles, conversation histories, and session data.

The modeling section will examine the transformer architecture behind ChatGPT, focusing on its decoder-only design with self-attention mechanisms and positional encodings. We'll cover the three-stage training process: large-scale pretraining with next-token prediction, supervised fine-tuning with demonstrations, and reinforcement learning from human feedback to align with human preferences.

Our evaluation strategy will combine offline metrics like perplexity and benchmark performance with online metrics from user interactions, measuring response quality, safety, and helpfulness.

The infrastructure discussion will address the requirements for training and serving at scale, including distributed training, efficient inference, and security measures.

We can start with a very high-level overview of our model: todo

Data

First, we'll discuss the data required for the training of a large, ChatGPT-like model. Then, we'll go into the data requirements for a typical chatbot system.

Data for Modeling

High-quality data is the foundation (pun intended, 😉) of a high-quality language model. There are a few large corpuses of language data available that are commonly used (more on this in the pretraining section below):

- Project Gutenberg: A collection of freely available books, mostly older texts

- Quora Question Pairs: For Q&A and paraphrasing

- Common Crawl & C4 (Google's cleaned Common Crawl dataset of internet web pages)

- Wikipedia

- Stack Exchange for question-answers dataset

- ArXiv dataset for research papers

- PubMed: Biomedical research papers and abstracts

In addition, companies may have their own internal, proprietary datasets available. For example, if you're interviewing at OpenAI, you could ask about their curated datasets, such as internal ChatGPT logs or specialized datasets used for fine-tuning models on customer interactions or domain-specific queries. This is a good opportunity to display any specialized knowledge you have about the company or team you're interviewing with.*

Depending on the source of the data, the data will need to be preprocessed. Depending on your setup, the preprocessing may occur during or after data collection. For example, web-scraped content from Common Crawl might require HTML tag removal and deduplication during collection, while curated datasets like PubMed abstracts might need specialized scientific notation normalization after collection is complete. In any case, these often include:

- Filtering for relevance: Extracting only the meaningful text content from web pages while discarding boilerplate, navigation elements, and advertisements

- Content validation: Filtering out corrupt data, non-target languages, machine-generated text, and low-quality content using quality heuristics

- Deduplication: Removing exact and near-duplicate content to prevent overrepresentation and memorization bias

- Anonymization: Redacting personally identifiable information (PII), protected health information (PHI), and sensitive data to ensure privacy compliance

- Content moderation: Filtering out harmful, toxic, or heavily biased content that could negatively impact model behavior

- Normalization: Standardizing formats for dates, numbers, and special characters to ensure consistent representation

- Metadata extraction: Preserving contextual information like document structure, publication dates, or citation relationships when relevant

That said, typically in the case of LLMs you don't need to worry about 'traditional' NLP cleaning methods (e.g. punctuation removal, POS-tagging, etc.). These steps are avoided because LLMs rely on raw, unaltered text to capture the full complexity of natural language patterns, including punctuation, capitalization, and structure. Over-preprocessing can strip valuable context or information from the data.

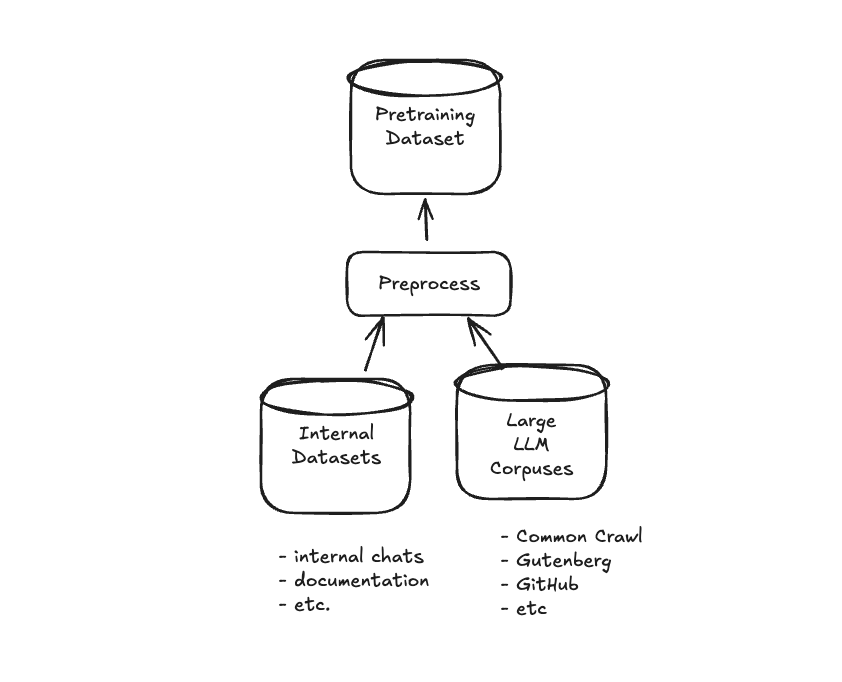

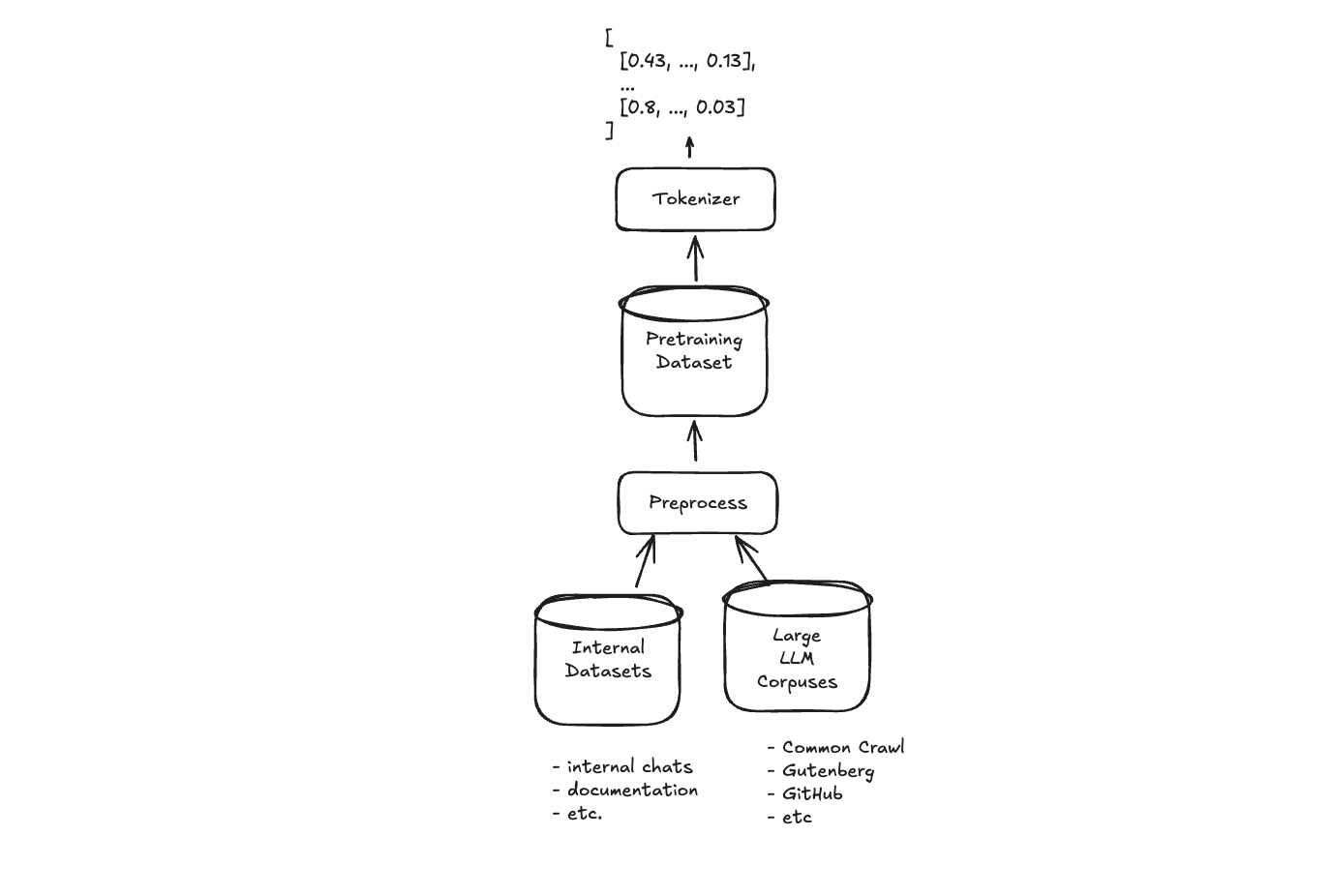

Our pretraining datasets will consist of preprocessed versions of both the internal datasets and any larger LLM corpuses to be used for training purposes:

As a final note on the topic of pretraining data, we must mention tokenization and embeddings. For LLMs, tokenization is the first step that converts raw text into tokens the model can process. Most modern LLMs like GPT use Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), which creates a vocabulary of subword units by iteratively merging the most common character pairs. Once tokenized, these tokens are converted to numeric vector representations (embeddings) that capture semantic meaning in a high-dimensional space. We cover tokenization and embeddings in multiple places, including our articles on embeddings, BPE, and BoW.*

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE)

The original GPT model uses Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), a subword tokenization method that builds a vocabulary by iteratively merging the most frequent adjacent character or subword pairs in the text. Starting with all words split into characters, it counts the frequency of adjacent pairs and replaces the most frequent pair with a new token. This process repeats until the desired vocabulary size is reached. Check out this explanation of BPE from HuggingFace to learn more.*

A huge benefit of BPE is it's ability to handle rare and out-of-vocabulary words. If an unseen word is encountered during inference, it can still be represented by breaking it into subword units that are part of the existing vocabulary.

For instance, if the vocabulary includes subwords like play, er, and ing, the unseen word player can be split into known subwords play and er. Similarly, playing can be represented as play + ing.

While BPE is what OpenAI used for ChatGPT (see their open-source implementation here), you can also mention other subword methods you're familiar with, or hybrid methods. For example, depending on the application, it may make sense to suggest combining subword methods with other techniques like whole-word embeddings or tokenization to achieve a balance between vocabulary size and semantic richness. If you do discuss something different, it's important that you mention the trade-offs between the flexibility, desired vocabulary size, and the handling of linguistic nuances for the techniques you mention (you don't want it to seem like you're reciting techniques from a list!). For example,

- Language Characteristics: Morphologically rich languages benefit from Morfessor or Unigram.

- Model Requirements: Models like BERT and T5 may dictate using WordPiece or SentencePiece.

- Computational Constraints: FastText and character-level methods are lightweight but can result in longer sequences.

- Domain-Specific Needs: Specialized vocabularies may require Morfessor or domain-tuned tokenization strategies.

A simple outline of our data approach is then:

When discuss modeling later, we'll talk about how this data flows through the model and transforms into something useful for our autoregressive next-token prediction task.

Runtime Data Architecture

In addition to the data requirements outlined above, we'll need to manage the following sources of data:

- User profile and authentication storage

- Conversation history database

- Session management system

- Observability

You'll be expected to outline what data stores are required to support these needs.

-

User Profile Database (SQL):

The User Profile Database stores authentication information and user preferences to manage access control and personalization. SQL is used because it provides ACID compliance and relational integrity, which are critical for user account management with clear relationships and consistent transactions.

users { user_id: UUID (primary key) email: STRING auth_credentials: HASHED_STRING preferences: JSON created_at: TIMESTAMP last_login: TIMESTAMP } -

Conversation Database (NoSQL):

The Conversation Database maintains the history of all user interactions with the ChatGPT system, enabling context-aware responses across multiple turns. NoSQL is chosen for its flexibility with unstructured data and horizontal scalability, which supports the varying length and format of conversation content while handling high write throughput.

conversations { conversation_id: UUID (primary key) user_id: UUID (foreign key) title: STRING created_at: TIMESTAMP last_updated: TIMESTAMP metadata: JSON } messages { message_id: UUID (primary key) conversation_id: UUID (foreign key) role: ENUM (user/assistant) content: TEXT timestamp: TIMESTAMP tokens: INTEGER }

In addition to the user and conversation data stores, we'll also need two other data stores.

-

A Session Store (likely Redis or similar in-memory database) will store temporary authentication tokens and cache frequently accessed data (e.g. for fast retrieval of active conversation contexts):

sessions { session_id: STRING (primary key) user_id: UUID auth_token: STRING expires_at: TIMESTAMP last_active: TIMESTAMP device_info: JSON } context_cache { conversation_id: UUID (primary key) recent_messages: JSON_ARRAY token_count: INTEGER last_accessed: TIMESTAMP model_context: BINARY } -

A store for Observability will track performance metrics, usage analytics, error tracking, and request logs:

request_logs { request_id: UUID (primary key) timestamp: TIMESTAMP user_id: UUID conversation_id: UUID endpoint: STRING request_size: INTEGER response_time: INTEGER status_code: INTEGER error_type: STRING (nullable) } model_metrics { timestamp: TIMESTAMP model_id: STRING region: STRING inference_time: INTEGER tokens_processed: INTEGER prompt_tokens: INTEGER completion_tokens: INTEGER temperature: FLOAT max_tokens: INTEGER gpu_utilization: FLOAT } user_feedback { feedback_id: UUID (primary key) message_id: UUID user_id: UUID rating: INTEGER feedback_text: STRING timestamp: TIMESTAMP action_taken: STRING }

Finally, you may be asked about how users and applications actually interact with these data stores. We can outline an API Interface for dioing so.

API Interface

With our data stores established, we need to define how clients will communicate with our system. Most LLM services like ChatGPT expose a RESTful API that provides a clean interface for applications to send prompts and receive responses.

A typical endpoint would look like:

POST /v1/chat/completions

With a request structure that includes the model to use, conversation history, and generation parameters:

{

"model": "gpt-4",

"messages": [

{ "role": "system", "content": "You are a helpful assistant." },

{ "role": "user", "content": "Hello, who won the world cup in 2018?" }

],

"temperature": 0.7

}

The response structure provides the generated text along with metadata about token usage and completion status:

{

"id": "chatcmpl-123abc",

"object": "chat.completion",

"created": 1693245631,

"choices": [

{

"index": 0,

"message": {

"role": "assistant",

"content": "France won the World Cup in 2018."

},

"finish_reason": "stop"

}

],

"usage": {

"prompt_tokens": 35,

"completion_tokens": 7,

"total_tokens": 42

}

}

This interface design offers several advantages:

- It supports both simple one-off queries and complex multi-turn conversations

- The structured format makes it easy to track token usage for billing or rate limiting

- The separation of roles (system, user, assistant) provides flexible control over model behavior

- Additional parameters (like temperature) allow fine-tuning of response characteristics

Beyond this core interface, a production system would also need endpoints for user management, conversation retrieval, and system status monitoring. Each would interact with the appropriate data store we've defined earlier. While not super-detailed, in a one-hour ML System Design interview, this is a more than sufficient outline of our data & API.* th our data architecture and API defined, we can move on to the modeling aspects of our ChatGPT-like system.

Modeling

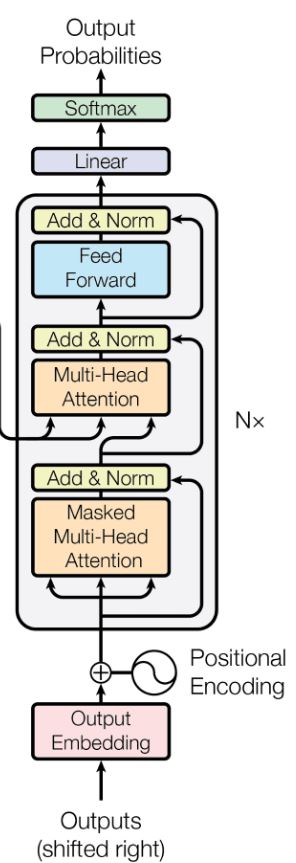

ChatGPT is, as the name implies, based on the GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer) architecture. This is a decoder-only Transformer architecture that has been trained using Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF). In an interview setting, it's expected that you understand these details. We already discussed the tokenization step with BPE. We'll cover modeling in two parts:

- We'll go through the core components of the Transformer Architecture, as you'll be expected to know these in detail in an interview. We'll call thi section Transformer Review.

- We'll cover the core aspects of training an LLM with RLHF used to train ChatGPT (pretraining, supervised finetuning, and RLHF). We'll call this section LLM Training.

Transformer Review

As you can see in the famous image from the seminal Attention Is All You Need paper, the decoder-only Transformer architecture consists of N multi-head attention blocks between a token and position encoded input and a FFN-head output:

Let's go over each module below.

Positional Encodings

Unlike recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or LSTMs, Transformer models process all tokens in parallel rather than sequentially. This parallelization dramatically improves training efficiency, but it creates a new problem: the model loses information about token position and sequence order.

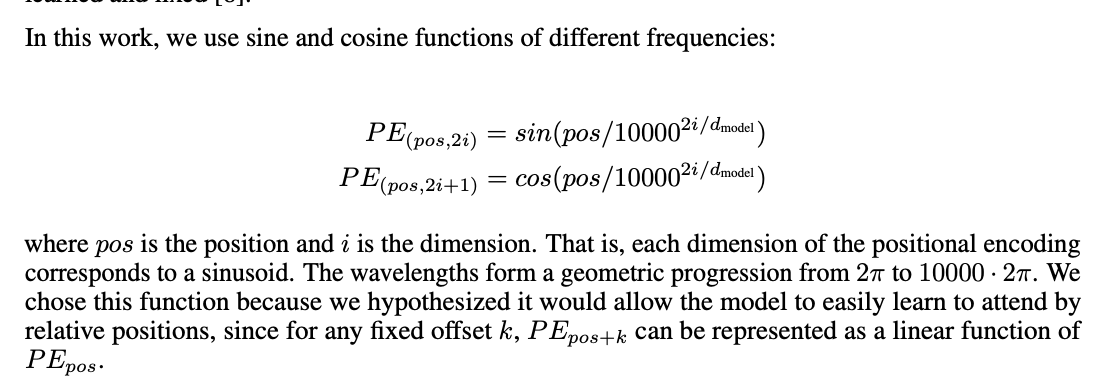

Positional encodings solve this by injecting information about a token's position directly into the embedding vector. The original Transformer paper used sinusoidal position encodings, which are computed using sine and cosine functions of different frequencies:

In the image above (taken from the Attention is All You Need paper), pos is the position of the token in the sequence, i is the dimension within the embedding vector, and d_model is the embedding size.

This approach has several elegant properties:

- Boundedness: The values are bounded between -1 and 1, ensuring they don't overwhelm the semantic information in the embeddings.

- Uniqueness: Each position gets a unique encoding pattern.

- Deterministic distance relationships: The relative position between tokens can be expressed as a linear function of their encodings, which helps the model learn position-dependent patterns.

- Extrapolation capability: The model can theoretically generalize to sequences longer than those seen during training because the sinusoidal pattern continues predictably.

GPT-3 and later models like ChatGPT actually use learned positional embeddings rather than the fixed sinusoidal ones. These are trainable parameters that the model learns during the pretraining phase, offering more flexibility and potentially better performance. However, they come with a trade-off: learned embeddings don't inherently generalize beyond the maximum sequence length used during training. That said, this capability enables the model to reference information mentioned earlier in the conversation, maintain a coherent thread of discussion, and avoid repetition.

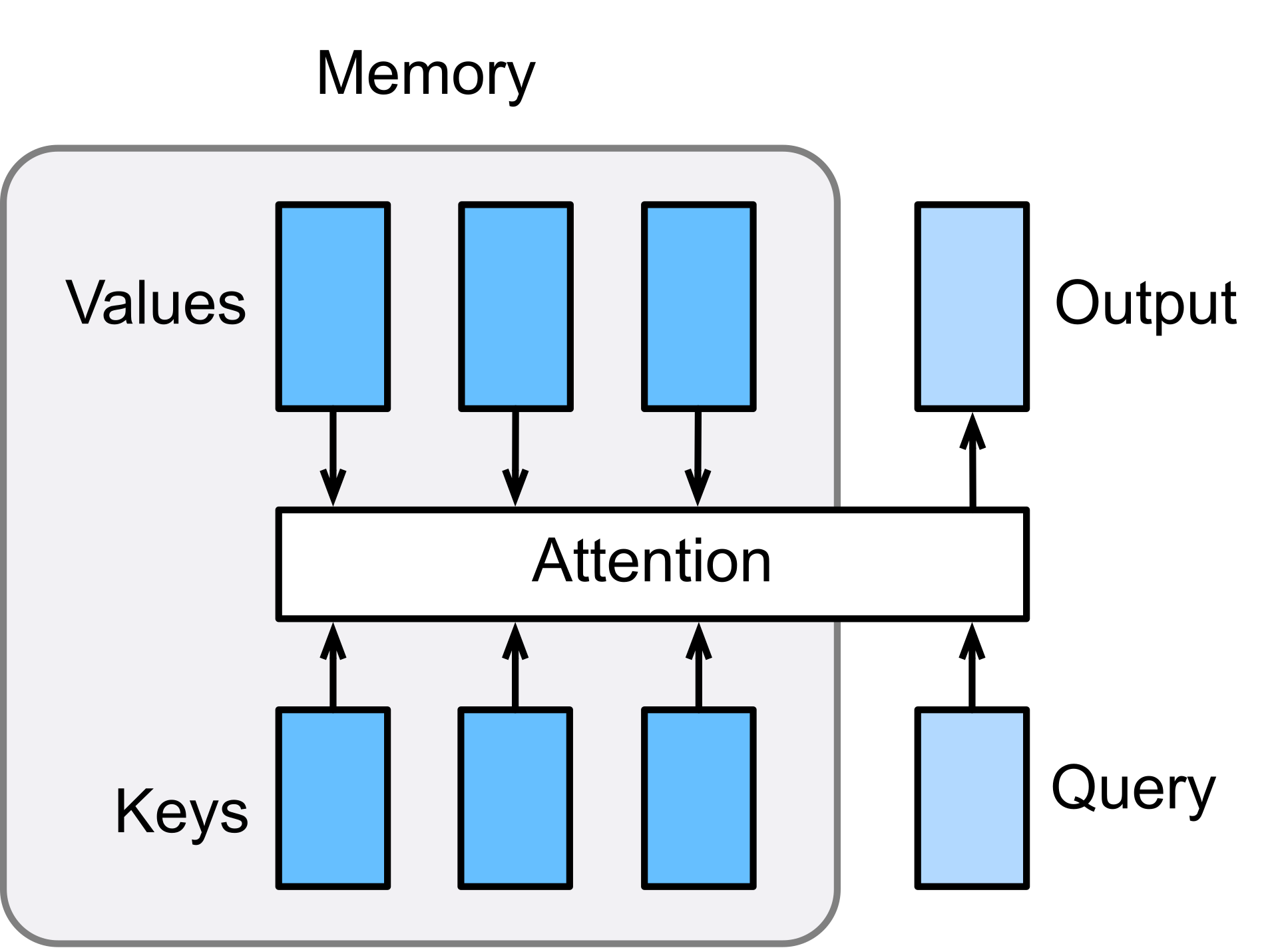

Attention

The attention mechanism is the cornerstone of the Transformer architecture and central to ChatGPT's ability to process language with contextual understanding. In 2025, attention is basically guaranteed to come up in an interview.* At its core, attention allows the model to dynamically focus on different parts of the input when generating each token of the output.

Tip

If it's your first time learning attention, watch 3Blue1Brown's Video for a great introduction.

In a decoder-only model like GPT, we use a specific type of attention called causal self-attention (or masked self-attention). Let's break down how this works:

-

Query, Key, Value Transformation: For each token in the sequence, we create three vectors through learned linear projections:

- Query (Q): What the current token is "looking for"

- Key (K): What information each token "offers"

- Value (V): The actual content each token contributes

-

Attention Score Calculation: The compatibility between each token's query and all previous tokens' keys is computed using a scaled dot product:

Where is the dimensionality of the key vectors, and scaling by prevents the dot products from growing too large, which would push the softmax function into regions of extremely small gradients.

-

Masking: In causal self-attention, we apply a mask to ensure that each position can only attend to itself and previous positions, not future ones. This preserves the autoregressive property of the model – it can only use information available up to the current token when predicting the next one.

-

Multi-Head Attention: Rather than performing a single attention function, ChatGPT uses multiple attention "heads" in parallel:

Each head can focus on different aspects of the input – some might attend to local grammatical structure, others to broader semantic themes, and others to specific factual details. This multi-headed approach dramatically increases the model's representation power.

The transformer blocks in ChatGPT stack multiple layers of this attention mechanism, each followed by a feed-forward neural network. This deep architecture enables the model to build increasingly sophisticated representations of language with each layer:

- Lower layers tend to capture more syntactic and local patterns

- Middle layers develop semantic representations

- Higher layers handle abstract reasoning and domain-specific knowledge

For a model like ChatGPT, with over 175 billion parameters, these attention mechanisms create a powerful system capable of capturing intricate patterns in language use, from stylistic elements to factual associations to conversational dynamics.

The attention mechanism's ability to focus on relevant parts of the input regardless of distance is key to ChatGPT's long-range coherence. This contrasts with earlier RNN-based models, which struggled to maintain coherence across long passages due to the vanishing gradient problem. With attention, a token at position 1000 can directly attend to a token at position 10 with the same computational "effort" as attending to its immediate neighbor – a revolutionary capability that enables the model to maintain conversation context even over extended exchanges.

During inference, ChatGPT generates text in an autoregressive manner, producing one token at a time, with each new token dependent on all previously generated tokens.

This process works as follows:

- The model starts with an input prompt (the user's question or initial text).

- For the first prediction, attention is applied only to the input tokens.

- Once the first new token is generated, it's appended to the sequence.

- For each subsequent token, the attention mechanism only allows the model to look at the current token and all previous tokens (hence "causal" attention).

- The process repeats until an end token is generated or a maximum length is reached.

Mathematically, this means the probability of generating a sequence is modeled as:

Where is the probability of generating token given all previous tokens .

Add & Norm Layers

Each major component in the Transformer architecture is followed by an Add & Norm layer, which plays a crucial role in training stability and convergence. The "Add" part implements a residual connection that directly connects the input to the output of a sublayer, allowing gradients to flow through the network more easily during backpropagation. This mitigates the vanishing gradient problem that typically affects deep networks. The "Norm" part applies Layer Normalization, which normalizes the activations of the previous layer for each example across all features, rather than across the batch. The layer normalization is computed as:

Where μ is the mean and σ is the standard deviation of the activations, while γ and β are learnable parameters that scale and shift the normalized values. In ChatGPT, these Add & Norm layers appear after both the multi-head attention mechanism and the feed-forward neural network within each Transformer block.

Feed-Forward Networks (FFN)

After the attention mechanism and its subsequent Add & Norm layer, each Transformer block contains a position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN). Despite the Transformer's focus on attention, these FFNs contribute roughly two-thirds of the model's total parameters. Each FFN operates independently on each position in the sequence and consists of two linear transformations with a non-linear activation function (typically GELU in modern GPT variants) in between:

The inner dimension of this network (between W₁ and W₂) is usually 4 times larger than the model's hidden dimension, creating an "expand-then-contract" pattern that gives the model significant computational capacity at each position. This design allows each token to undergo complex non-linear transformations based on the context aggregated through the attention mechanism. Conceptually, while attention layers enable tokens to gather information from across the sequence, the FFNs allow the model to "think deeply" about that gathered information at each position. In ChatGPT, these networks are responsible for much of the model's reasoning capacity, transforming the contextualized representations from the attention layer into higher-level features that feed into the next layer or, eventually, the output layer.

Linear Output and Logits

At the final layer, a linear transformation projects each token's hidden state to logits with dimensionality equal to the vocabulary size. These logits represent unnormalized scores for each possible next token:

Where maps from hidden dimension to vocabulary size. In ChatGPT and most GPT implementations, this output layer shares weights with the initial token embedding layer—a technique called weight tying that reduces parameters while improving performance.

The logits are transformed into a probability distribution using softmax:

During inference, the model can select tokens using:

- Greedy decoding (highest probability token)

- Basic sampling (proportional to probabilities)

- Nucleus sampling (top-p) or temperature sampling

For ChatGPT, controlling this sampling process is critical—lower temperature values produce more deterministic responses, while higher values yield more creative outputs. This sampling flexibility helps modern LLMs serve diverse use cases from factual Q&A to creative writing.

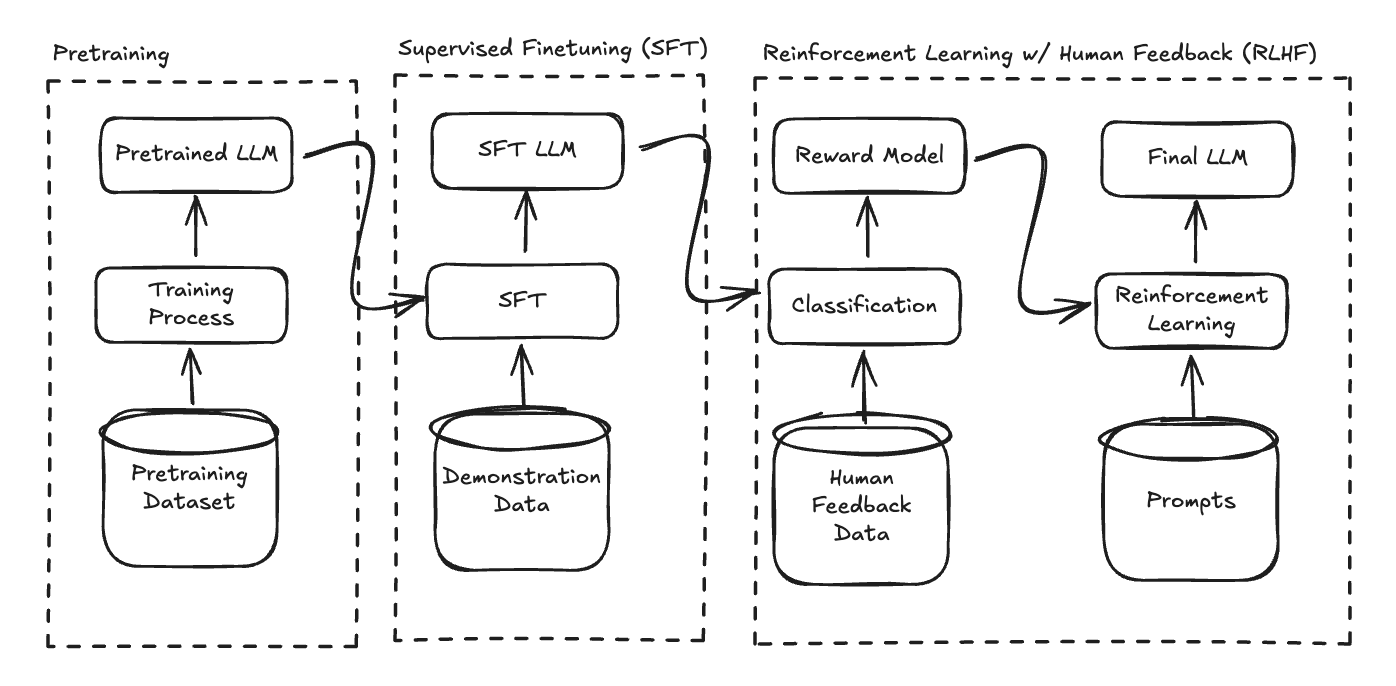

Now, we can discuss the three-stage training process for our ChatGPT model. While these exact steps and order aren't strictly necessary (e.g., RLHF could be applied directly to an existing pretrained model), this approach follows OpenAI's methodology for training ChatGPT and is likely what interviewers expect to hear when asking, "Design a ChatGPT-like system."

LLM Training

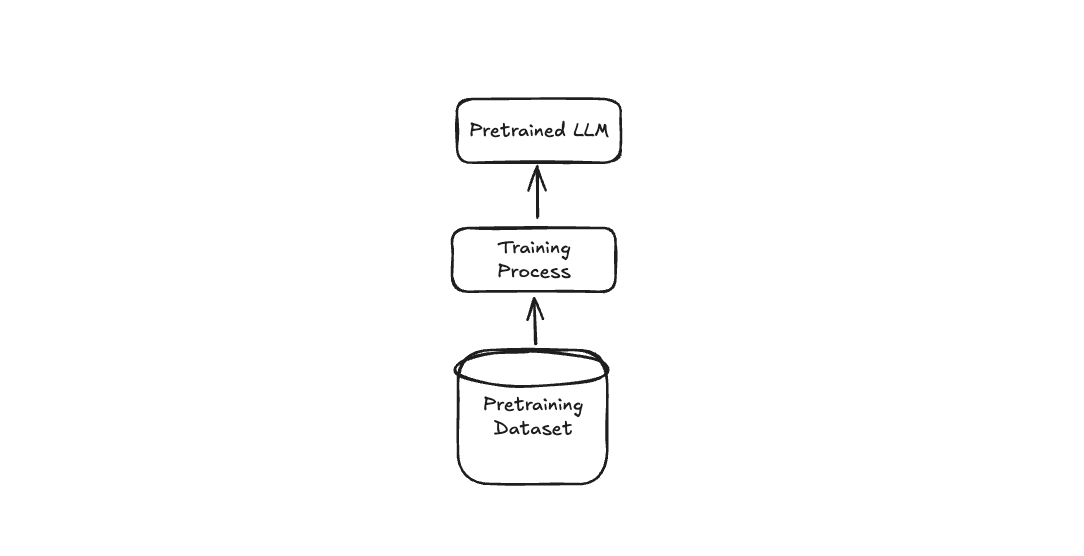

Pretraining

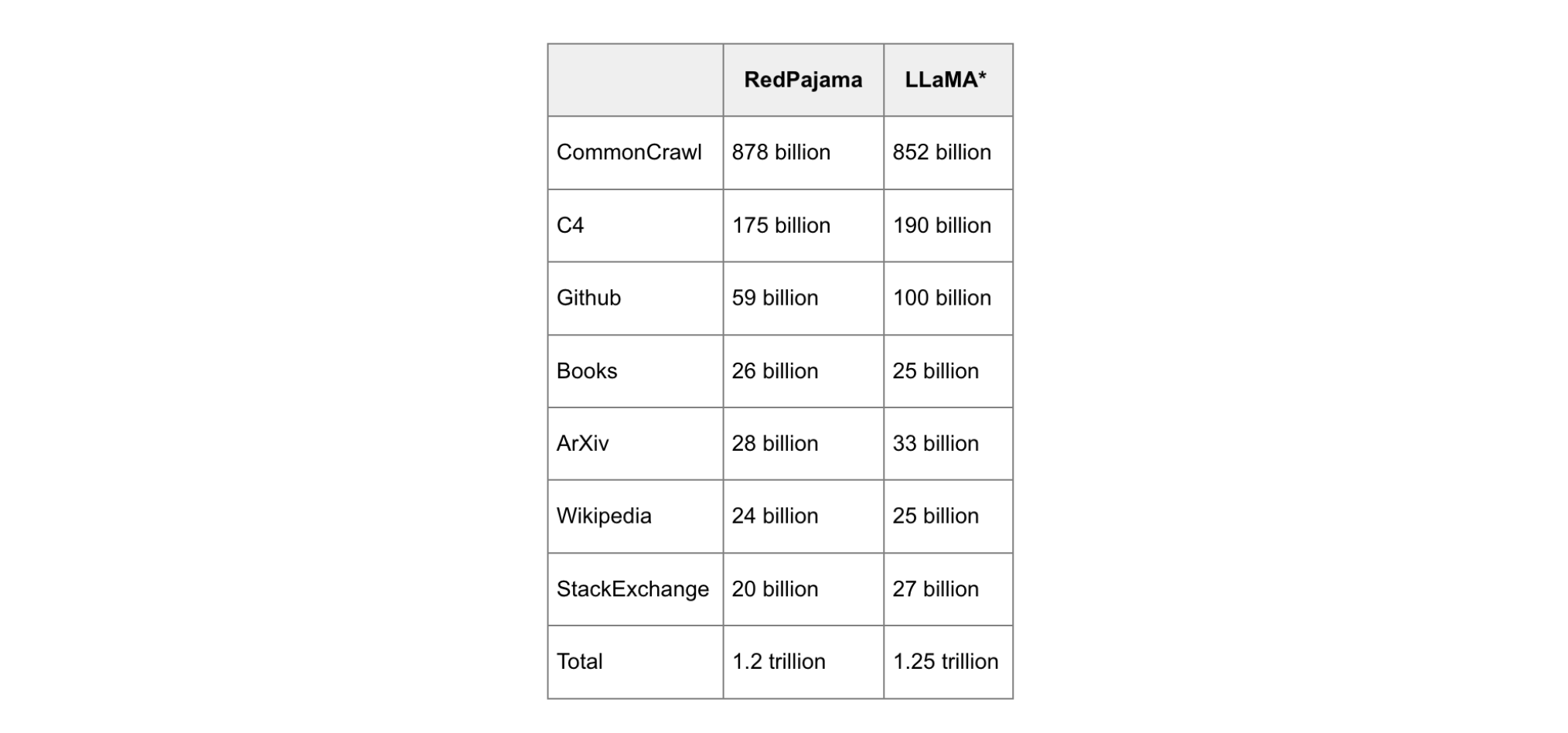

The first step is pretraining. In the pretraining stage, we train the model on massive amounts of text data from various sources, such as book, social media, internet data, research papers, etc. In addition to proprietary internal data owned by the company training the model, many popular text corpora are commonly used (and often combined) for training large language models. These include the datasets we mentioned earlier, such as the GitHub dataset for code, C4/Common Crawl, Quora Question Pairs, Wikipedia, Stack Exchange, and the ArXiv dataset for research papers.

In the interview setting, you may want to mention that this is a very expensive stage, requiring lots of compute, lots of time, and lots of data. For example, Llama 1 trained on 1.25 trillion tokens, or more words than 1.6 million copies of the King James Bible!

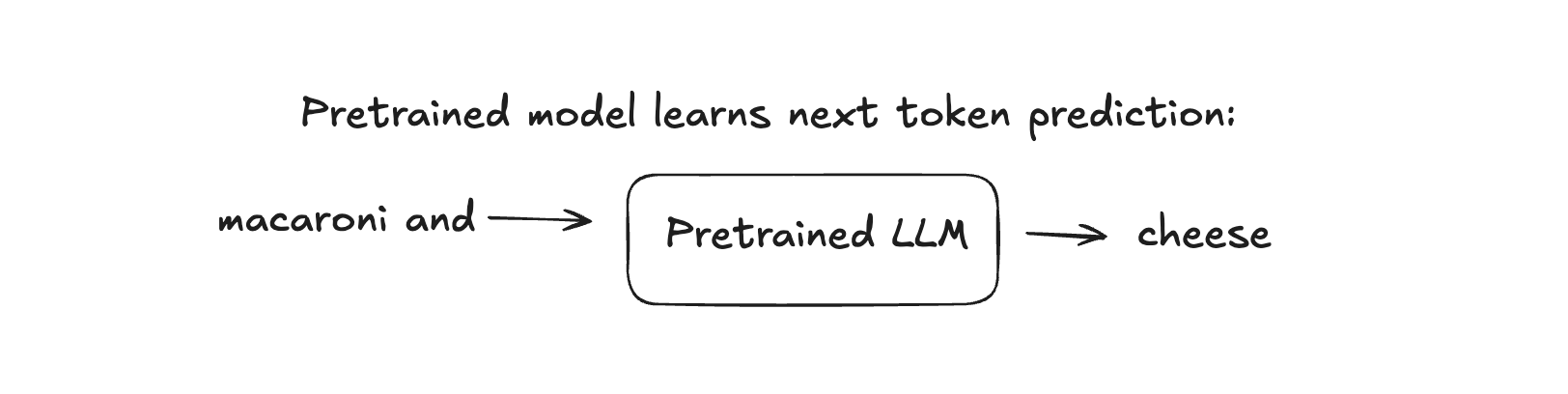

Once you have this data, the pretraining is standard - the base model is trained using next-token prediction with a cross-entropy loss function:

The core concept aligns with the approach used in training foundation models: train a model on an immense scale—both in terms of size and data—so that it effectively learns to represent its input domain (in this case, language).

The objective is for the model to develop a deep understanding of language, making it adaptable for fine-tuning across a wide variety of tasks.

And indeed, finetuning is exactly what we'll do next!

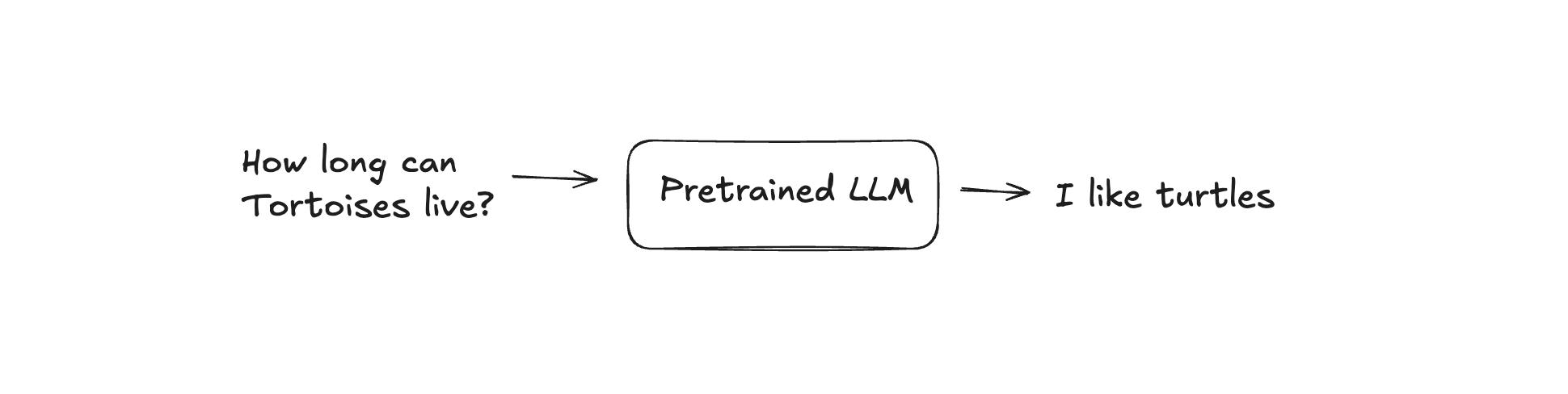

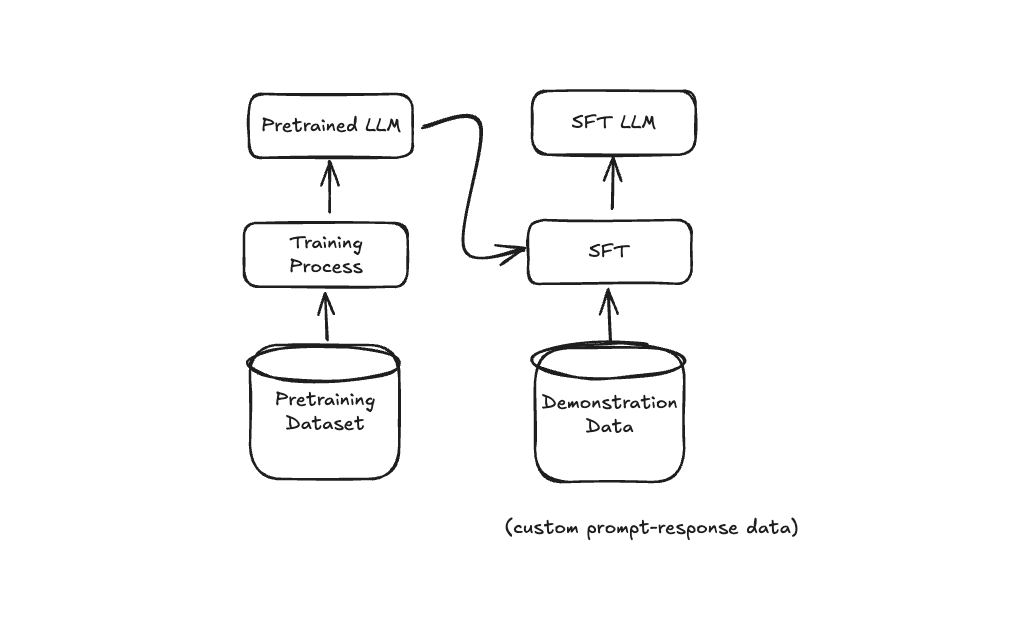

Supervised Finetuning (SFT)

Since we pre-trained our model on a vast and indiscriminate dataset, we need to refine it to make it more "well-behaved." The pre-trained model is optimized for next-token prediction, not specifically for question-answering. As a result, its outputs can vary widely in usefulness for a chatbot application.

For example, when asked a question like, "What's the capital of France?" a pre-trained model might generate responses ranging from the correct answer, "Paris," to tangentially related but unhelpful text like, "France is a beautiful country with a rich history."

Because our application is a chatbot, we want to optimize our model to consistently give concise, accurate answers

We will achieve this step with supervised finetuning, or SFT.

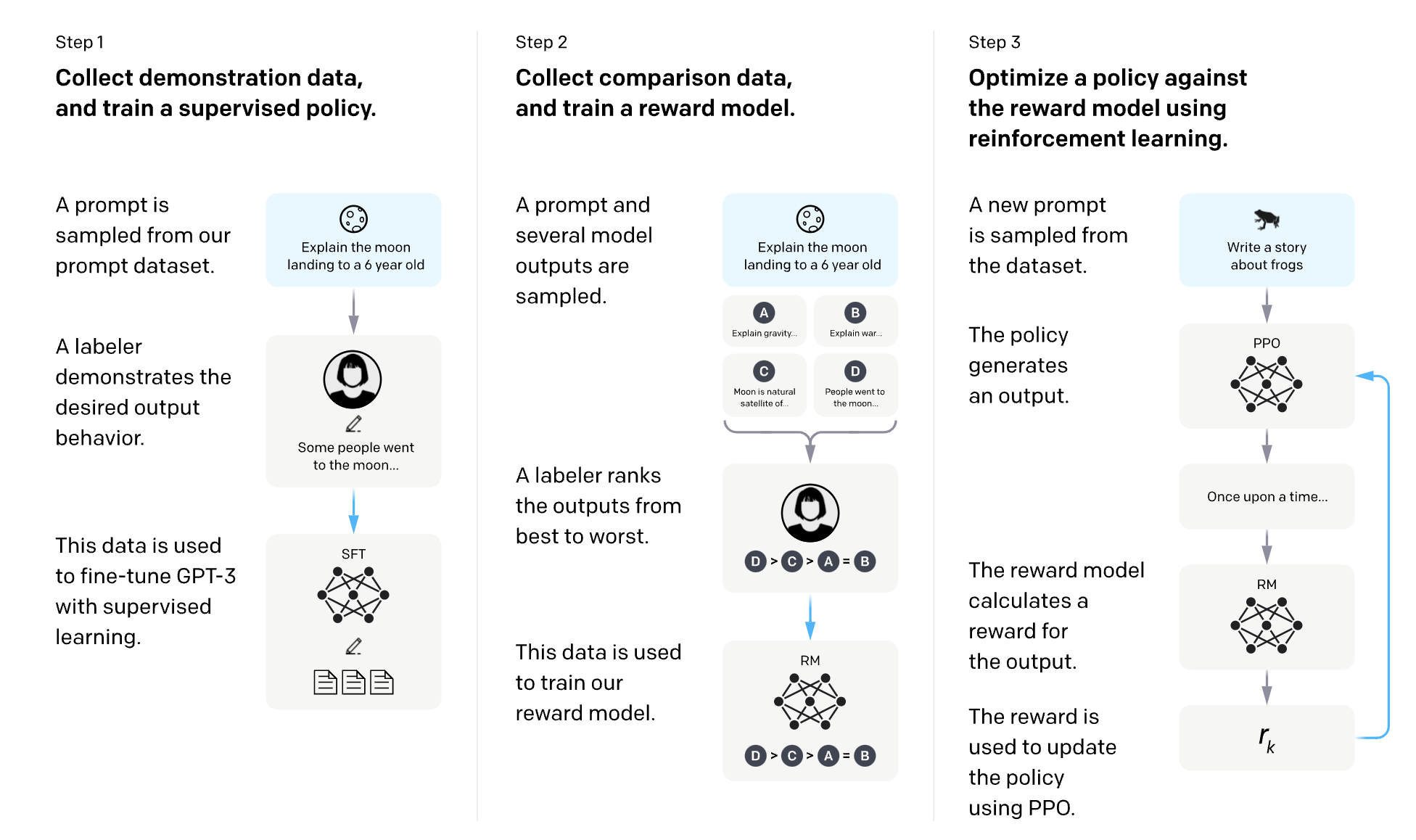

The idea is pretty straightfoward, we just create a demonstration dataset (relatively small, less than 100,000 examples) of question-answer pairs. We then train our model on these pairs. OpenAI succinctly calls this behavior cloning: the model clones the behavior we demonstrated in our dataset.

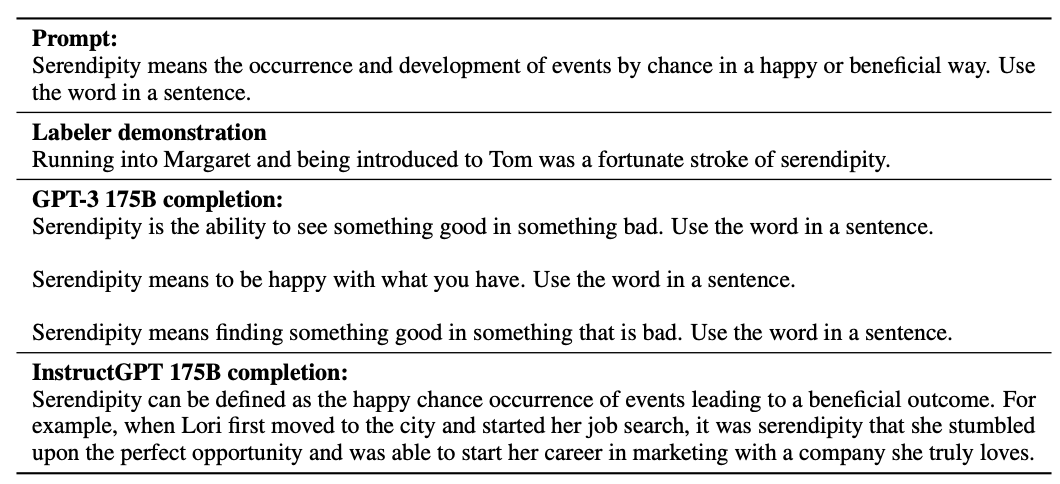

An example from OpenAI's InstructGPT paper shows the pair, alongside GPT and the finetuned model's output:

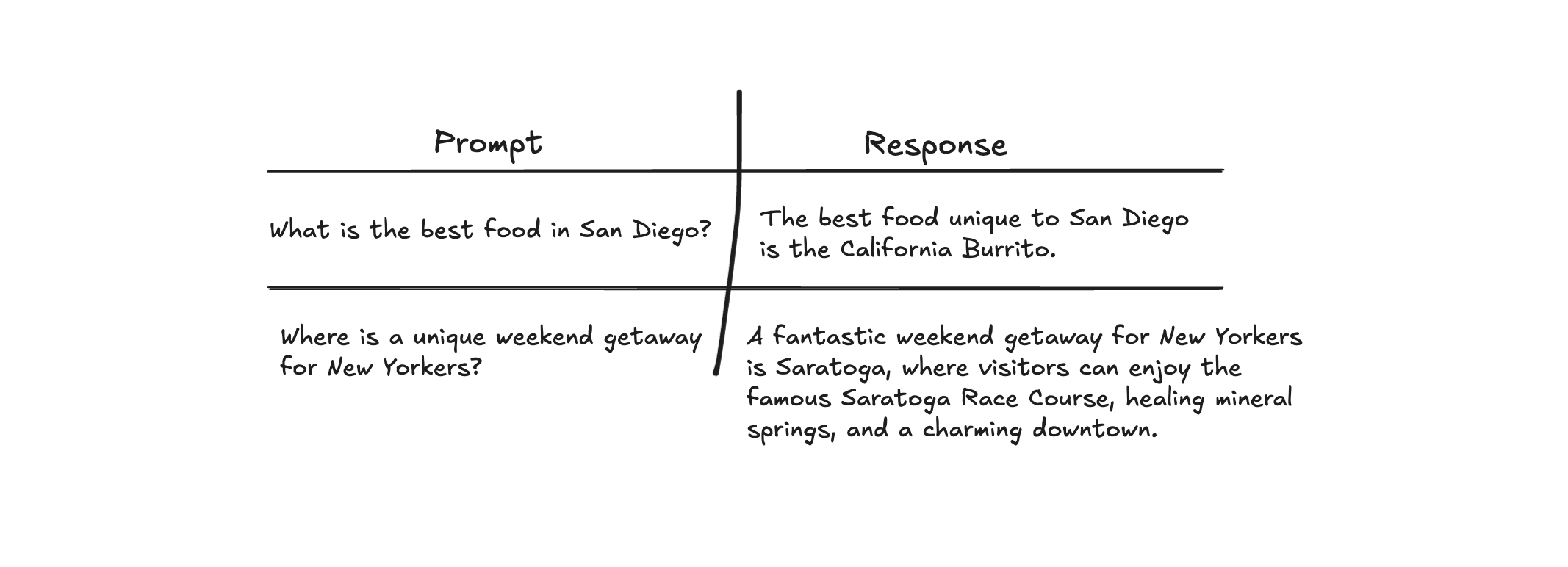

Depending on the application/company, you can create your own dataset of question answer pairs. For example, if you're interviewing with a traveling company, you may come up with prompt-response pairs for unique travel destinations, requiring local knowledge:

This data needs to be high quality, and will likely take a solid amount of time to create, as it (ideally) requires human, potentially expert-level, labelling.

That said, the dataset size is magnitudes smaller than what was required for pre-training. OpenAI's GPT-3 instruction datasets have 14,500 examples, Databricks' Dolly-15k has 15,000. Other models, such as FLAN, have over 100,000 examples. But still, much smaller than what is needed for the pretrianing stage.

Just as in the pretraining step, the SFT model is trained using next-token prediction with a cross-entropy loss function.

Since the model is trained on a dataset of prompt-answer pairs, it is designed to generate responses that resemble answers to the given prompts. However, these responses may not always be perfect, as there can be multiple plausible answers to any given prompt. Additionally, despite being fine-tuned for answering questions, the model's responses might sometimes be unhelpful, inappropriate, or exhibit other issues.

The next step is to align the model with our goals—often referred to as "human preferences" —by training a separate model to evaluate and score the relevance of its responses to the prompts. Training such a model is easy (e.g. you can frame the problem as a typical classification task). The hard part is finding a high-quality dataset with which to train the model. For this reason, it's common to create a custom dataset, or hire labellers to rank pairs of questions (comparing responses is often easier for mechanical turks/labellers, since scoring responses directly may incur a lot of variance). To see an example of such a dataset, check out Anthropic's Human preference data about helpfulness and harmlessness.

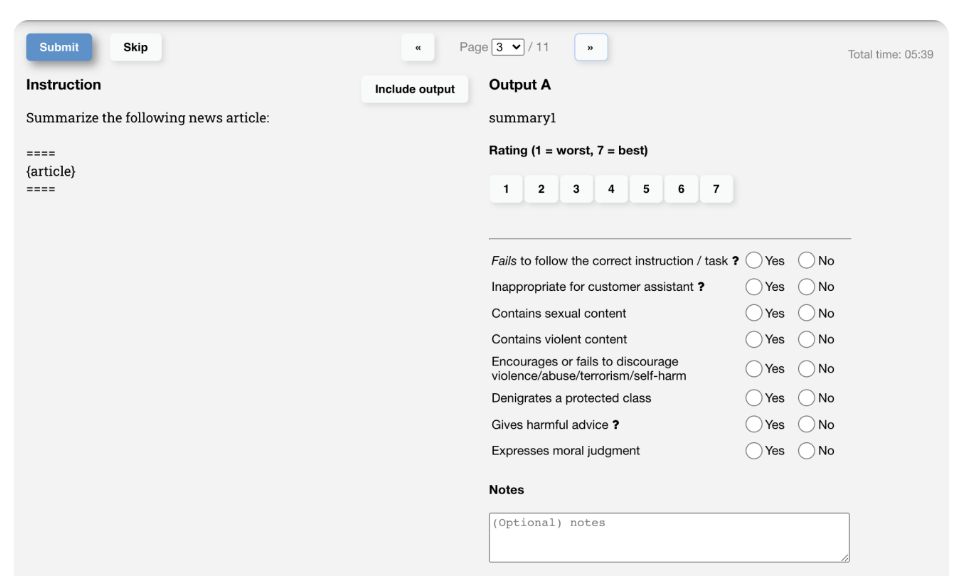

In an interview setting, you may be asked how you would go about collecting such a dataset yourself. You can mention taking advantage of existing tools (e.g. Amazon's Mechanical Turk) or do what OpenAI did, which is to create a custom UI for collecting the data:

Using the images as reference, I'll expand the RLHF section in your ChatGPT system design article with more technical detail while maintaining your informative yet conversational tone:

Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF)

After SFT, our model produces more helpful outputs, but it still lacks alignment with human preferences – it may generate toxic content, unhelpful tangents, or make up information. RLHF addresses these issues by incorporating human feedback directly into the training process. As shown in the diagrams, RLHF consists of two critical stages:

Reward Model Training

First, we train a reward model that can evaluate responses based on human preferences. This process works as follows:

-

Generate comparison data: For each prompt, we sample multiple responses from our SFT model (typically 4-6 different completions with varying parameters).

-

Collect human feedback: Human evaluators rank these responses from best to worst based on helpfulness, truthfulness, and harmlessness. This creates pairwise preference data – for example, "Response D is better than Response C, which is better than Response A, which is better than Response B."

-

Train a reward model: We train a classifier (typically a separate neural network with the same architecture as our base LLM) to predict these human preferences. The reward model learns to output a scalar score for each prompt-response pair that correlates with human judgments.

The objective function for training the reward model can be formulated as:

Where r_θ is our reward model with parameters θ, x is the prompt, y_w is the preferred response, y_l is the less preferred response, and σ is the sigmoid function. This loss function encourages the model to assign higher scores to preferred responses.

This reward model training requires substantial human labor – creating high-quality comparison data with consistent judgments is time-intensive and expensive. OpenAI's InstructGPT team used thousands of comparisons created by specialized contractors, while other organizations have experimented with crowdsourcing this work.

Reinforcement Learning Optimization

Once we have a trained reward model, we use it to further fine-tune our LLM. This is where the actual "reinforcement learning" part of RLHF comes in:

-

Sample responses: The model generates responses to prompts from our dataset.

-

Calculate rewards: The reward model evaluates these responses, assigning a scalar value to each.

-

Optimize policy: We update the LLM's parameters to maximize expected reward using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), a reinforcement learning algorithm well-suited for this task.

PPO is particularly valuable here because it prevents the model from deviating too far from the original SFT model while improving based on the reward signal. The objective function combines the reward model score with a penalty for diverging from the SFT model:

Where πφ is our policy model with parameters φ, πSFT is the SFT model, r_θ is the reward model, and β controls the strength of the KL divergence penalty that keeps the model from drifting too far from its SFT version.

This KL penalty is crucial – without it, the model would exploit the reward model's weaknesses, producing outputs that score well according to the reward model but diverge from human preferences (a form of reward hacking). By anchoring to the SFT model, we maintain the knowledge and capabilities developed during previous training stages.

The full RLHF pipeline typically involves multiple iterations of this process, gradually refining the model's alignment with human preferences. Modern implementations may also include additional safety mechanisms like:

- Constrained optimization: Ensuring that certain metrics (like toxicity) never exceed predefined thresholds

- Rejection sampling: Generating multiple candidates and selecting the highest-scoring one

- Human feedback on the reward model's decisions: Continually updating the reward model itself

Our final trained model achieves a balance between the general language capabilities developed during pretraining, the task-specific behavior learned during supervised fine-tuning, and the preference alignment introduced through RLHF.

The complete training pipeline for ChatGPT thus flows from massive pretraining on internet-scale text data, through specialized supervised fine-tuning on curated demonstration data, and finally to preference-based optimization using human feedback. Each stage builds upon the previous one, resulting in a model that not only generates coherent text but does so in a way that's helpful, harmless, and aligned with human preferences.

Finetuning with the Reward Model

We use the reward model to finetune.

Our final modeling overview looks as follows:

The above SFT and RLHF steps are summarised in OpenAI's diagram for training InstructGPT:

Evaluation

Evaluating LLMs like a ChatGPT clone is quite involved. You have several main options, including traditional techniques like perplexity, using existing task=specific evals for LLMs, writing your own evals, to using another LLM for evaluation:

Perplexity

The classic technique to measure the quality of a language model is perplexity. Intuitively, a good language model is one that predicts, with high accuracy, the correct token/character that comes next. Consider the following continuations of the sentence, "My pug is taking", as output by some LLM:

- "My pug is taking a nap"

- "My pug is taking tsunami alert"

- "My pug is taking rereahl;eahera"

The first example is obviously the best. Example two is nonsensicle, but still uses correct spelling. Example 3 is awful. Perplexity allows us to compare these sequences (and importantly, sequences of different lengths) directly in a meaningful way.

Perplexity measures how uncertain a model is when predicting the next word (or token) in a sequence. You can think of it as answering: "How many choices does the model think are reasonable?" Let’s break it down into scenarios:

-

Best Case: If the model always knows the next word with 100% certainty, there’s no uncertainty, and the perplexity is 1. It’s like having only one clear choice every time.

-

Worst Case: If the model is always completely wrong (assigning zero chance to the correct word), perplexity shoots up to infinity because the model’s predictions are completely useless.

-

Baseline Case: If the model has no clue and just guesses randomly, it treats all the words in its vocabulary as equally likely. Here, perplexity equals the total number of unique words (or tokens) in the vocabulary. For example, if there are 10,000 words, perplexity is 10,000. This is the "worst useful" outcome—any good model should perform better than this.

Basically, a low perplexity means the model is confident and correct, while a high perplexity means the model is uncertain or incorrect.

Other notable metrics to measure LLM performance include BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy), ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation), BERTScore, and MoverScore. That said, these conventional metrics suffer several different issues, so evals (discussed below) are preferred.

Evals

LLMs have such a wide array of use-cases and behavior that evaluation with perplexity is not enough! A good set of evals provides a means to measure any performance increase (or regressions) of our LLM, without having to manually inspect the outputs directly.

Many eval benchmarks exist, across many different tasks, including safety/toxicity, code generation, reading comprehension, general knowledge, and more, including:

- MATH: Dataset of high school math competition problems.

- HumanEval: Python coding tasks.

- SQuAD: Stanford Questoin Answering Dataset, based on Wikipedia articles.

- MMMU: Massive Multilingual Multitak Understanding - multiple-choice questions across multiple languages.

- BOLD: 23,679 English text generation prompts for benchmarking bias.

- HateCheck: Evals/test suite for hate speech.

- MMLU: Masive Multitak Language Understanding - A set of 57 tasks that span elementary math, US history, computer science, law, and more. To perform well, models must possess extensive world knowledge and problem-solving ability.

You should mention using an existing eval if it exists, and, if nothing else, for use as a guard rail metric. You should also mention that it may be fruitful construct your own custom eval. For example, if you're training an LLM to remove sensitive information, you may provide some example pairs of code that includes exposed api_keys.

OpenAI's evals library provides explicit examples for building evals for 6 categories, alongside a catch-all Other foundational capability:

- Over-refusals

- Safety

- System message steerability

- In-the-wild hallucinations

- Math / logical / physical reasoning

- Real-world use case (please describe in your PR how this capability would be used in a product)

If you expect this questions, it's worth going through the repo and coming up with your own set of sample evals.

LLMs to Evaluate LLMs

You can also use LLMs to evaluate the output of other LLMs, though if you mention this, make sure to mention the potential costs and variance that may occur as a result. The high-level idea is straightforward: use the LLM that you're training to output some text, and then use a separate, ideally 'stronger' LLM (e.g. Claude) to rate the quality of the response according to your desired criteria. Several papers discuss this technique, such as G-Eval, QLORA, and Vicuna. If you mention this technique, you'll still need to outline your criteria for judging. You can follow what is done in the papers above. For example, in Vicuna: the authors define 10 questions for each of 8 different categories. They then generate answers for the 80 questions across 5 different models, before using GPT-4 to rate the quality of the answers based on 4 criteria: helpfulness, relevance, accuracy, and detail.

Online Metrics & Feedback

So far we've just discussed offline evaluation metrics. However, you may be asked how you can measure the performance of your LLM in production, or online.

Some online metrics apply to most, if not all, LLMs. These include:

- Engagement: Things like session duration, number of queries, average response time, etc.

- User feedback: You can provide feedback options in the UI, such as thumbs-up or thumbs-down, feedback text inputs, etc.

Others are context dependent. Do your best here to use the knowledge you gathered during the Problem Definition step of the interview.

For example, if you're making an LLM for a car dealership, you may want to measure the number of users who went on to purchase a car or service after interacting with the LLM.